You are here:

PacLII >>

Databases >> Vanuatu - Review of National Land Legislation, Policy and Land Administration 2007

Vanuatu - Review of National Land Legislation, Policy and Land Administration 2007

Download PDF version [471 KB]

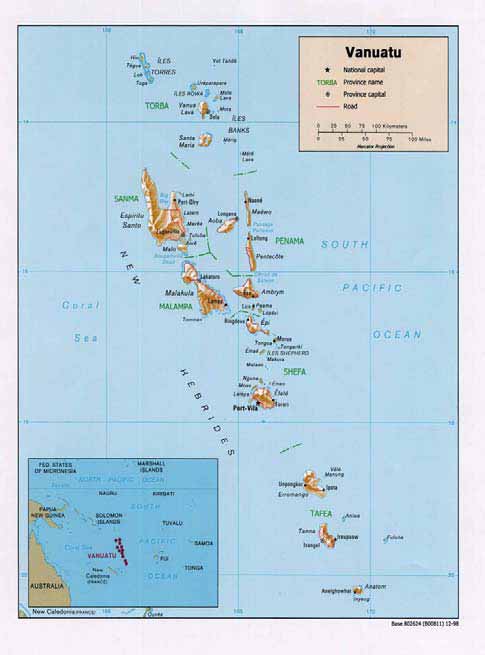

Vanuatu

Review of National Land Legislation, Policy and Land Administration

Chris Lunnay

Jim Fingleton

Michael Mangawai

Edward Nalyal

Joel Simo

Map

Table of Contents

Abbreviations

Executive Summary

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. The National Land Summit

1.2. The Steering Committee

1.3. Technical Assistance Support

2. SUMMARY OF STATUS OF LAND AFFAIRS IN VANUATU

2.1. National Land Summit

2.2. Policy development

2.3. Legislation

2.4. Land administration

2.5. Basic needs

2.6. Doing Business in Vanuatu

3. LAND POLICY AND LEGISLATION

3.1. At the time of independence

3.1.1. The Constitution 1980

3.1.2. Land Policy Communiqué 1980

3.1.3. Land Reform Regulation 1980

3.1.4. Ministerial Statement on Land Policy implementation 1980

3.2. Since independence

3.2.1. Alienated land Act 1982

3.2.2. Land Leases Act

3.2.3. Land Acquisition Act 1992

3.2.4. Land Reform (Amendment) Acts 1992 and 2000

3.2.5. Urban Lands Act 1993

3.2.6. Freehold Titles Act 1994

3.2.7. Strata Titles Act 2000

4. REVIEW OF THE LAND POLICY AND LEGISLATION

5. LAND-RELATED LEGISLATION

5.1. Land Surveyors Act 1984 (as amended)

5.2. Valuation of Land Act 2002

5.3. Land Valuers Registration Act 2002

5.4. Land dispute settlement

5.4.1. Customary Land Tribunals Act 2001

5.5. Physical planning and foreshore development

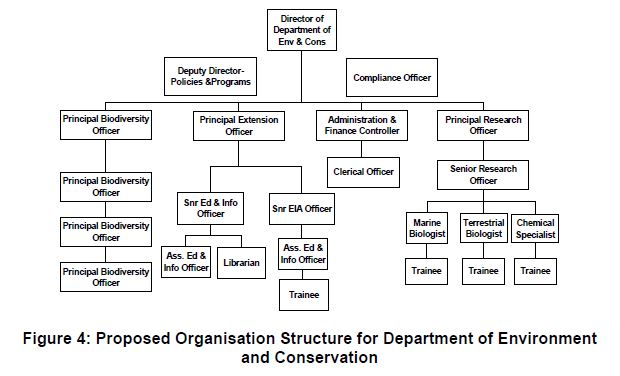

5.6. Environment protection

6. LAND ADMINISTRATION

6.1. Land Use Management and Land Administration

6.2. Institutional and Organisational Issues

6.2.1. Organisation, Management and Operations (OMO)

6.2.2. Decentralisation

6.2.3. Overlap and Duplication of Responsibilities

6.2.4. Municipal and Provincial Government

7. REFORMS NECESSARY TO IMPLEMENT THE NATIONAL LAND SUMMIT RESOLUTIONS - ACTION MATRIX

7.1. Land Ownership

7.2. Fair dealings

7.3. Certificate to negotiate

7.4. Power of the Minister over disputed land

7.5. Strata title

7.6. Agents/Middle men or women

7.7. Lease rental and premium

7.8. Sustainable development

7.9. Conditions of lease

7.10. Public access

7.11. Enforcement

7.12. Zoning

7.13. Awareness

8. IMPLEMENTATION AND DIRECTION

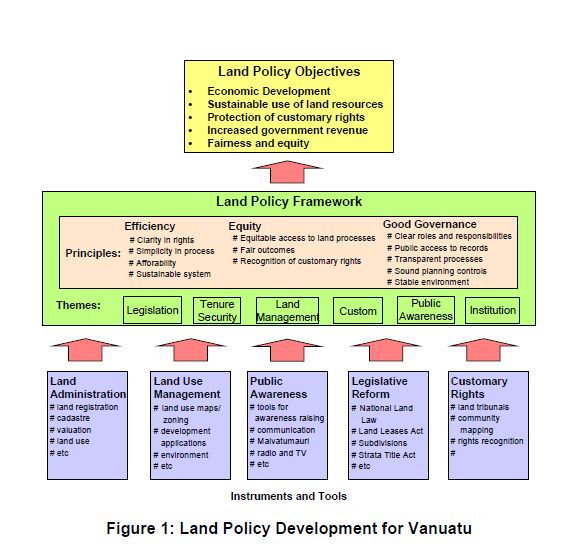

8.1. Land Policy Development

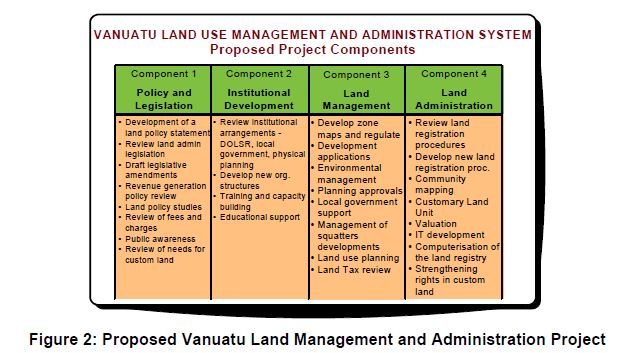

8.2. Long Term Initiative

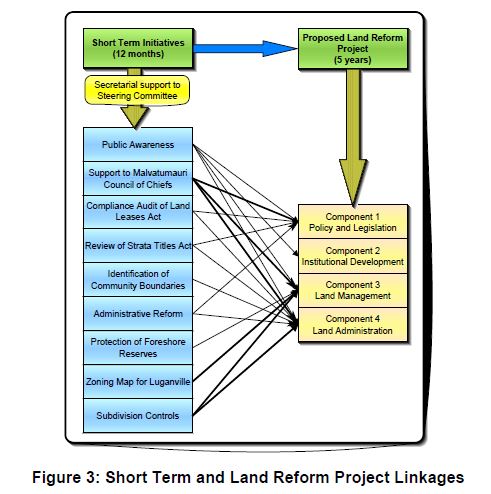

8.3. Short Term Reforms/Initiatives

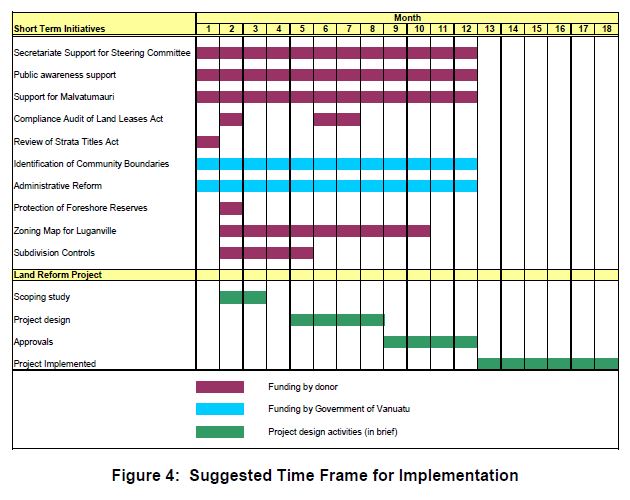

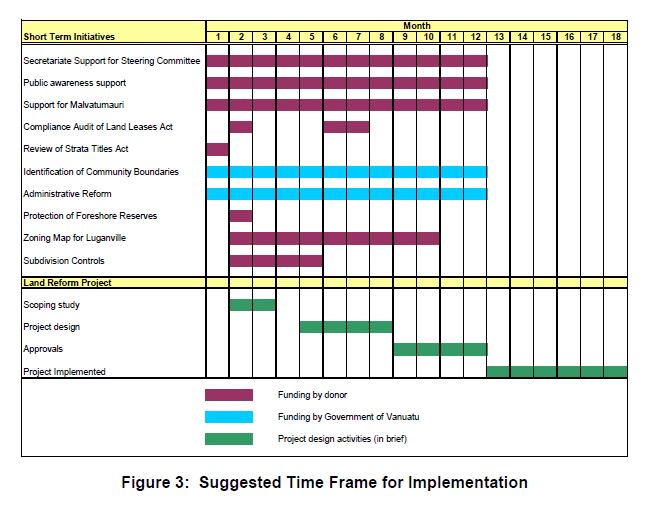

8.4. Time Frame

Attachments

Attachment

1: Interim Transitional Strategy and Future Plans to Implement the

Resolutions of the National Land Summit 2006 (English version)

Attachment

2: Interim Transitional Strategy and Future Plans to Implement the

Resolutions of the National Land Summit 2006 (Bislama version)

Attachment 3: Council of Ministers Resolutions (English version)

Attachment 4: Council of Ministers Resolutions (Bislama version)

Attachment 5: Membership of the Steering Committee

Attachment 6: List of Relevant Legislation

Attachment 7: Land Administration and Land Use Management Activities in Vanuatu

Attachment 8: Action Matrix - National Land Summit Resolutions

Attachment 9: Reforms of Land Legislation

Attachment 10: Project Design Concept and Short Term Support Initiatives

Attachment 11: Scoping Notes for Short Term Initiatives

Attachment 12: List of meetings

Attachment 13: Terms of Reference for Technical Assistance Support

Abbreviations

AusAID Australian Agency for International Development

CARMA Community Area Resource Management Activity

COM Council of Ministers

CRP Comprehensive Reform Program

DOLSR Department of Lands, Surveys and Records

LUPO Land Use Planning Office

MoL Ministry of Lands

NZAID New Zealand Aid

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development

OVG Office of the Valuer General

PAA Priorities and Action Agenda

REDI Rural Economic Development Initiative

TA Technical Assistance

VANRIS Vanuatu Resource Information System

VG Valuer General

VIPA Vanuatu Investment Promotion Authority

Executive Summary

The

National Land Summit in September 2006 marked a turning-point in

Vanuatu’s land affairs. The twenty-six years after independence were

marked not by land policy development, but by land policy decline. The

20 main resolutions endorsed by the Summit are evidence of serious

problems in such areas as agreements to lease custom land, lease

conditions, land use planning, subdivisions, registration

procedures, public access to beaches and rivers, and the public’s

awareness of land rights and laws.

The

review team was given the task of assisting the Government to advance

the outcomes of the Summit, and identifying the reforms and possible

assistance necessary to implement those outcomes, both in the

short term and the longer term. The team undertook this task under the

direction of a Steering Committee, during February-March 2007. This

report reviews Vanuatu’s present land policies and the main

legislation affecting land, either directly or indirectly, and the

present arrangements for land use management and administration.

The

report then identifies the reforms which the review team believes are

necessary, to implement the National Land Summit’s resolutions. First,

there is a need for policy development, not only to address

serious problems in the leasing of land to outsiders, but also to

address the emerging need for greater security of tenure for

ni-Vanuatu, and for land dealings between ni-Vanuatu. Problems in

lease arrangements have dominated the land agenda so far, but

ni-Vanuatu land needs will be a greater priority for the future.

Physical planning (or zoning) is a critical tool in efficient land use

management and sustainable development, but at present it is seriously

deficient, both in rural and urban areas. Foreshore development is

taking place without the necessary approvals, causing beach

erosion and preventing public access.

To

remedy the problems raised at the Land Summit, policies need to be

clarified, new legislation introduced, and some existing legislation

amended. What is required is not a sweeping revolution, but a

reinstatement of sound land tenure and land use principles, as well as

fairness and social equity. There is also a pressing need for

strengthening the land administration and land use management

arrangements. Partly this can be done by institutional reform, partly

by better coordination, partly by training and

capacity-building. Decentralisation is also important, but in

order to be effective it must be accompanied by organisation and

management reforms.

The

report contains a matrix, listing the 20 main resolutions from the Land

Summit, and the actions which the review team sees as necessary to

implement each of them. There is also a set of recommendations, for

consideration by the Steering Committee and further processing within

Vanuatu’s system for policy-making. These recommendations, some for

immediate and short-term action and others for the longer term,

are intended to maintain the momentum generated by the Land Summit, and

lay the basis for a comprehensive reform of the nation’s

land policies, laws and administration. A series of scoping notes

are provided for each of the short term initiatives to assist the

Steering Committee in submitting proposals for assistance. It

is also recommended that the Steering Committee appoint a

secretariat to support the development and implementation of the

proposed short term initiatives.

The

ultimate goal for the Steering Committee is to obtain support for a

land reform program that will assist in the implementation of the

numerous reform measures that need to be undertaken

to satisfactorily progress the 20 resolution from the National

Land Summit. Land reform is required in a number of key areas,

including legislation and policy, institutional development, land

use management and land administration. The drafting of a National

Land Law, as provided for in the Constitution, is a high priority and

which must be developed with widespread consultation but specifically

in consultation with the National Council of Chiefs (Malvatumauri).

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. The National Land Summit

In

July 2005, the Vanuatu National Self-Reliance Summit recommended the

holding of a National Land Summit to discuss land issues in relation to

national self-reliance. Vanuatu’s first National Land Summit was held

from 25-29 September 2006 in Port Vila, with the theme of "Sustainable

Land Management and Fair Dealings to Ensure Progress with Equity and

Stability”. Organised by the Ministry of Lands and the Vanuatu

Cultural Centre, a series of six Provincial land summits were held in

the months leading up to the National Summit to broadly consult

about the definition of customary ownership, fair dealings and the

role of Government. The goal of the National Land Summit was to agree

on resolutions on which to form the basis of a new land policy for the

next five to ten years.

The Vanuatu National Land Summit was a

highly successful exercise in participatory decision-making, on the

most important and sensitive of all subjects - land. The Land Summit

provided direction and commitment from various stakeholders to

addressing key issues such as customary land ownership, lease

agreements, physical planning and decentralisation. The Summit

concluded with twenty resolutions, categorised under the following

headings:

- Land ownership.

- Fair dealings.

- Certificate to negotiate.

- Power of the Minister over disputed land.

- Strata title.

- Agents/Middle men or women.

- Lease rental and premium.

- Sustainable development.

- Conditions of lease.

- Public access.

- Enforcement.

- Zoning.

- Awareness.

The

twenty resolutions of the National Land Summit have been included in a

document "Interim Transitional Strategy and Future Plans to Implement

the Resolutions of the National Land Summit 2006" that has been

prepared following the summit and endorsed by the Council of Ministers.

The Interim Transitional Strategy document is included as Attachment 1

(English version) and Attachment 2 (Bislama version). As well as

the twenty resolutions, the document:

- imposed a temporary

moratorium on subdivisions, surrendering of existing agricultural

leases and the power of the Minister when land is in dispute;

- introduced temporary administrative measures; and

- set out a long term development plan.

On the 21 November 2006, the Council of Ministers endorsed:

- the transitional strategy;

- the establishment and composition of a Steering Committee;

- a commitment to find support for funding to implement the resolutions; and

- endorsed

changes that had been made to the 20 resolutions by the Council of

Ministers (see Attachment 3 for English version and Attachment 4 for

Bislama version).

1.2. The Steering Committee

To

maintain the momentum generated by the National Land Summit and to

assist in progressing discussion and action in relation to land issues

the government has formed a Steering Committee. The role of the

Steering Committee is to provide oversight and to monitor and manage

the process of moving forward activities against the resolutions, for

ultimate presentation to the Government. The committee has a broad

membership including government representatives, the Malvatumauri

(National Council of Chiefs), the Vanuatu Cultural Centre, women’s

groups, youth groups and private sector representation. A list of

membership of the Steering Committee is included as Attachment 5.

1.3. Technical Assistance Support

The

Australian Government through the Australian Agency for International

Development (AusAID) has funded technical assistance to work with the

Steering Committee to progress the summit resolutions. The Terms

of Reference for the technical assistance is included as Attachment 13.

The overall objective of the assistance is to:

support

the Ministry of Lands in its review of the outcomes from the National

Land Summit, and identify the reforms and possible assistance necessary

to implement those outcomes, both in the short term and the longer

term.

The technical assistance team1

commenced the contract on 22 January 2007 and the first field visit to

Vanuatu was undertaken from 26 January through to 9 February 2007. A

draft of the technical assistance report was submitted to the

Steering Committee on 18 February 2007. A follow-up field visit was

undertaken from 21 to 28 February 2007 to enable

detailed discussions with the Steering Committee on the draft

report and recommendations and to undertake additional field visits and

meetings.

Working under the direction of the Steering Committee

the technical assistance team have used the framework of the twenty

resolutions from the National Land Summit as the basis

for consultations with key stakeholders and as a guide for

developing recommendations on possible assistance to implement the

outcomes of the Land Summit. The 20 resolutions have been used as

the framework for the development of an Action Matrix which outlines

all the actions necessary to address the resolutions (see Attachment

8). An extensive program of consultation was undertaken with

government officials, private sector, Malvatumauri (National Council of

Chiefs), village chiefs and officials, women’s groups and the youth of

Vanuatu. A number of site visits were also undertaken to locations such

as Mele, Pango, Eton, Takara, Santo and Tanna to gain an appreciation

of issues and also to discuss possible solutions to

the resolutions from the National Land Summit.

This report

provides a detailed analysis and review of the land policy and land

related legislation, reviews the land administration functions and then

outlines the reforms necessary to implement the National Land

Summit resolutions. The direction to be undertaken for the

implementation of a large reform project is outlined and details are

provided on the short term initiatives that are considered

necessary to maintain the momentum generated by the Summit. A number of

scoping notes are provided for the short term initiatives which will

assist the Steering Committee in sourcing support.

2. SUMMARY OF STATUS OF LAND AFFAIRS IN VANUATU

2.1. National Land Summit

The

convening of the National Land Summit, development of the interim

transitional strategy and establishment of the Steering Committee has

occurred at a critical time in the country’s land affairs. Over

recent years, the land reforms introduced at independence have been

largely undermined. Land alienations, which had played such a big part

in Vanuatu’s mobilisation for independence in 1980, have emerged

again on a scale which threatens the livelihoods of ni-Vanuatu, the

authority of the government, and the country’s social and political

stability. The seriousness of this review of the country’s land

policies, laws and administration must not be underestimated. It was

this concern which led the Vanuatu Self-Reliance Summit to recommend

the holding of a National Land Summit, to discuss the most important

land issues facing Vanuatu, and prepare a set of agreed resolutions

based upon the wishes of the people, to present to the national

leadership for formulation of a National Land Policy.

The twenty

resolutions from the National Land Summit highlight critical areas that

need to be addressed and which have received strong endorsement from

the people of Vanuatu. It is now the responsibility of the

Steering Committee to progress the resolutions in a responsive and

efficient manner on behalf of the people of Vanuatu. The reason for

urgent action is due to the critical state of affairs in the

weaknesses of the land policies, laws and administration.

2.2. Policy development

Policy

development on land has been weak over the years since independence.

There has been no clear statement of a new land policy since

independence, while the basic policy commitments made at that time

have been undermined in important respects. Perhaps the main underlying

reasons for this loss of direction were –

- the ambiguity surrounding the legal powers and responsibilities of the custom owners of land, and

- uncertainty over the Government’s role in relation to land dealings.

In

a country where, by the Constitution, the full land ownership of the

custom owners was entrenched, and dealings in land are carried out

directly between custom owners and outsiders, failure to address

this ambiguity and uncertainty made custom owners very vulnerable to

exploitation. Where the Government is given a role in land dealings

(eg, the Minister’s power of approving negotiators, and the

dealings which eventuate from direct negotiations), the powers have

frequently been abused. These policy weaknesses must be addressed, and

fortunately the Land Summit resolutions go a long way in

clarifying these basic matters.

2.3. Legislation

In

the absence of policy clarification of the above basic matters, it

follows that the land legislation is deficient in important respects.

Many new land laws have been passed by the Parliament since

independence, but much of the current legislation was designed to

handle the conversion of pre-independence titles to the new

postindependence regime, yet it remains the basic legal framework

for the country’s land system to the present day. Where there have been

legislative "innovations", one was aimed at converting urban land to

individual freehold ownership (against the spirit, and probably

the letter, of the Constitution), and another was the introduction of a

strata titles regime – a law whose defects have allowed a spate

of "unofficial" subdivisions.

2.4. Land administration

The

Department of Lands, Surveys and Records has grown to provide a range

of land services, some common-place (eg, surveys) but others more

particular to Vanuatu, and more demanding. The latter include

advising the Minister in the exercise of powers to approve negotiators

and the land dealings which eventuate from negotiations (advice which

the Minister is not obliged to accept), involvement in settling

land disputes, and land use planning (the latter powers being exercised

at provincial level). Officials suffer from the usual problems of lack

of resources to carry out their functions adequately, but they are

also affected by the policy and legislative ambiguities and

uncertainties referred to above. In a proposed land dealing, it

is unclear who the Lands Officer is supposed to be acting for –

the custom owners? the other members of the land-owning group? the

local community? the State? The interests of these stakeholders

are often in conflict.

The above is only a very brief outline of

the deficiencies which undermine achievement of the three main themes

of the Land Summit – sustainable land management, fair dealings in

land, and progress with equity and stability. This report will

provide a more thorough review of Vanuatu’s current policies, laws and

administrative systems affecting land ownership, management

and development.

2.5. Basic needs

Land

dealings in Vanuatu (negotiations, leases, registrations,

sub-divisions, etc) have got out of control in recent years, and the

resolutions of the National Land Summit require that they

be brought back under control. This will mean difficult decisions,

not only because there has probably been a high level of non-compliance

with legal requirements, but also because of the sheer volume of

land dealings coming before official bodies for approval. Options which

will be considered include:

- a moratorium on further processing of new dealings (a temporary moratorium is already in place);

- an inquiry into the legality of recent dealings, with a view to recommendations for remedying the situation;

- more

aggressive application of the remedies currently available – forfeiture

of leases, prosecutions for breach of public access and zoning laws,

etc.;

- amendments of legislation, possibly with retrospective effects;

- as a last resort, compulsory acquisitions.

Each

of the above options entails a degree of risk (including ‘sovereign

risk’), which will have to be weighed against the benefits of regaining

control over the nation’s land affairs.

2.6. Doing Business in Vanuatu

In "Doing Business in 2007"2,

the difficulties faced in undertaking business activities in Vanuatu

are highlighted. Of the data on 175 countries, Vanuatu is ranked at

58th in doing business. However in relation to trade, employment

and land registration Vanuatu is ranked in the bottom half of all

countries. These statistics highlight that there are a number of areas

where Vanuatu needs to focus attention if it is to improve

business and land administration activities.

In relation to

registering property it is stated that to register a land parcel (a

lease) it takes on average 188 days which is compared with 31.8 days in

OECD countries. The cost in Vanuatu to register is approximately 7% of

the property value which is compared with 4.3% for OECD countries.

These figures reinforce some of the concerns expressed by the National

Land Summit and highlight the importance of Vanuatu commencing

action immediately to address a review of land related legislation and

procedures in land administration.

3. LAND POLICY AND LEGISLATION

3.1. At the time of independence

For

present purposes, land policy development in Vanuatu can be regarded as

beginning on the eve of independence in 1980. Under the previous

British-French Condominium, different approaches were taken

to land development at different times, and the two governments were

pursuing conflicting goals during the preindependence period. Whereas

the British were following a decolonisation agenda, the French

were resisting moves in that direction, and as a consequence very

little had been done by the joint colonial administration to prepare

the country for selfgovernment.

Involvement by ni-Vanuatu

in economic development had been minimal. Independence in 1980 was

achieved after a long struggle, and in fact was accompanied by a

rebellion, which was only put down with outside military

assistance.

3.1.1. The Constitution 1980

The

Vanua’aku Pati won the 1979 election with an overwhelming majority, and

set the course for independence on 30 July 1980. The Constitution

adopted at independence had been hastily prepared under difficult

circumstances, but its provisions on land in Chapter 12 reflected the

central issue in the struggle for independence – return of alienated

lands to their custom owners. Thus, it provides:

- Article 73: "All land in the Republic of Vanuatu belongs to the indigenous custom owners and their descendants."3

- Article 74: "The rules of custom shall form the basis of ownership and use of land in the Republic of Vanuatu."

- Article

75: "Only indigenous citizens of the Republic of Vanuatu who have

acquired their land in accordance with a recognised system of land

tenure shall have perpetual ownership of their land."

- Article

76: "Parliament, after consultation with the National Council of

Chiefs, shall provide for the implementation of Articles 73, 74 and 75

in a national land law and may make different provision for

different categories of land, one of which shall be urban land."

- Article

77: "Parliament shall prescribe such criteria for the assessment of

compensation and the manner of its payment as it deems appropriate to

persons whose interests are adversely affected by legislation

under this Chapter."

- Article 78: "(1) Where,

consequent on the provisions of this Chapter, there is a dispute

concerning the ownership of alienated land, the Government shall hold

such land until the dispute is resolved.

"(2)

The Government shall arrange for the appropriate customary institutions

or procedures to resolve disputes concerning the ownership of custom

land."

- Article 79: "(1) Notwithstanding Articles 73,

74 and 75, land transactions between an indigenous citizen and either a

non-indigenous citizen or a non-citizen shall only be permitted with

the consent of the Government.

"(2) The consent required under Sub-article (1) shall be given unless the transaction is prejudicial to the interests of –

a) the custom owner or owners of the land;

b) the indigenous citizen where he is not the custom owner;

c) the community in whose locality the land is situated; or

d) the Republic of Vanuatu."

- Article 80: "Notwithstanding Articles 73 and 74, the Government may own land acquired by it in the public interest."

- Article

81: "(1) Notwithstanding Articles 73 and 74, the Government may buy

land from custom owners for the purpose of transferring ownership of it

to indigenous citizens or indigenous communities from

over-populated islands.

"(2)

When redistributing land in accordance with Sub-article (1), the

Government shall give priority to ethnic, linguistic, customary and

geographical ties."

Notable features of these constitutional provisions are –

a) the primacy given to "custom", "custom owners" and "indigenous citizens" (ni-Vanuatu) in land tenure and land use;

b) the apparent "self-acting" effect of Art. 73, in returning all land in Vanuatu to its custom owners;

c) the ambiguity over the nature of "custom ownership" – on the one hand suggesting that it is group-based (all land belongs to "the indigenous custom owners and their descendants" – Art. 73), while on the other hand suggesting that it is individual-based (prejudicial to the interests of the indigenous citizen, "where he is not the custom owner" – Art. 79(2)(b));

d) the combination of a freedom for custom owners to deal directly with their land, with a responsibility

on the Government to prevent transactions which are prejudicial to the

interests of the custom owners, the local community or the

national interest (Art. 79);

e) the provision that,

notwithstanding the general position that all land in Vanuatu belongs

to the custom owners (Art. 73), the Government may own land acquired by

it "in the public interest" (Art. 80);

f) the requirement

that Parliament, after consultation with the National Council of

Chiefs, "shall provide for the implementation of Articles 73, 74 and 75

in a national land law" (Art. 76).

As already mentioned, the Constitution

was prepared in less than ideal circumstances, and the intention was

that any ambiguities and uncertainties would be resolved in the

upcoming National Land Law.

3.1.2. Land Policy Communiqué 1980

On 24 April 1980, three months before independence, the Minister of Lands, Sethy Regenvanu, issued the Government’s Land Policy Communiqué. After referring to these forthcoming constitutional provisions, he made a number of elaborations, including that –

- there would be three categories of land – rural, urban and public;

- rural land

would be owned according to custom, and companies or nonindigenous

citizens could lease it directly from its custom owners, subject to

Government consent;

- before giving its consent, the Government would make sure that –

- the groups owning the land have heard about, discussed, understood and agreed to the lease";

- "the representatives chosen by the group to negotiate the lease have been authorised by the group to do so"; and

- "the lease is in the interests of the custom owners, local people, and the country";

- once the Government had consented to a rural lease, it would guarantee the security of the lease;

- the Government would hold a perpetual lease of urban and public land,

with the custom owners of the land entitled to a continuing share of

the revenue from the land, continuing ownership of certain areas

of urban land to develop or lease themselves, and continuing

representation on statutory bodies managing the land;

- public land would be land needed for public purposes like schools, hospitals and airfields;

- the length of leases would depend on the land use – rural leases would normally be for 30 years, urban leases for 50 years, and leases for "big investment projects" for up to 75 years;

- joint venture agreements could be entered into with custom owners to develop rural land.

3.1.3. Land Reform Regulation 1980

On Independence Day, the Land Reform Regulation 1980 came into operation.4

In its "long title" it is called a measure "to make interim provision

for the implementation of Chapter 12 of the Constitution". Article

73 of the Constitution

had effectively abolished all existing land titles, and the main

purpose of the Regulation was to provide for their replacement in

certain circumstances. To qualify as an "alienator", a person had

to have a freehold or other beneficial interest in the land, be in

occupation of the land, and have maintained the land

and improvements in reasonably good condition (Sec. 1). The

Regulation conferred on such alienators an entitlement to remain in

occupation of the land, until either a lease agreement was negotiated

with the custom owners or payment was made for improvements to the land

(Sec. 3).

The Regulation also made provision for the negotiation

of agreements between former title-holders and custom owners, for their

continued occupation of the land. In order to enter

into negotiations, alienators had to apply for a Certificate

of Registered Negotiator, using the application form set out in

the Land Reform (Rural Alienated Land) Regulations 1980.

The Certificate had to state the names of the applicant and the

custom owners, brief details of the land the subject of negotiations

and the object of the negotiations (Sec. 6). The Minister of Lands

was given powers of "general management and control" over land in three

situations –

a) where the land

was occupied by an alienator, and either there was no approved

agreement with the custom owners or the custom ownership was disputed;

or

b) the land was not occupied by an alienator, but the custom ownership was disputed; or

c) the land was not occupied by an alienator, but in the opinion of the Minister the land was inadequately maintained (Sec. 8).

The

Minister was given the power to conduct transactions over such lands,

including the granting of leases on behalf of the custom owners (Sec.

8(2)). The Minister could also apply to an Island Court to decide

on the ownership of the disputed land (Sec. 5(2)).

Section 14 provided –

"When

a lease is registered in a register in the Records Office the

registration of that lease shall be evidence of the validity of the

lease and the details thereof."

This was the Government’s

"guarantee" given to the security of leases, until such time as a new

registration system was introduced (as it was in 1983, by the Land Leases Act, see below).

The

foregoing arrangements applied mainly to rural lands. In the case of

urban land, much of this was owned at independence by the British or

French Governments, the Condominium or a municipality. All such

land came within the definition of "State land" in the Land Reform Regulation

(Sec. 1), and vested in the Government as public land at independence

(Sec. 9). Provision was made for payment of compensation to the

custom owners of such land (Sec. 11).

3.1.4. Ministerial Statement on Land Policy implementation 1980

On 29 October 1980, three months after independence, the Minister made a Statement

to Parliament on the implementation of the Land Policy. He referred to

the emphasis to that stage on alienated land – about 20% of all

land in the rural areas – and his intention to shift his attention to

the development of the remaining 80% of custom land as soon as

possible. Regarding alienated rural land, the Minister outlined

his intended approach to the identification of registered negotiators,

the custom owners and the object of negotiations between the two. In

the case of custom owners, what he said he was looking for was "general

agreement on which groups have interests under custom in a parcel of

alienated land, and appointment by them of their representatives,

or ‘negotiation team’, for the purpose of the negotiations".

Where

it was clear that the custom owners wished to proceed with

negotiations, the Minister said that he would be "looking for

development proposals which involve participation by

ni-Vanuatu nationals, in particular the custom owners." While

mentioning that the country’s agricultural policy, and the place of

foreign investors in that policy, was still not settled, the

Minister referred to three possible situations –

(i) for major development proposals: an agreement for up to 75 years, but on the basis of a joint venture with the custom owners;

(ii) for minor development proposals: a lease or joint venture agreement for up to 30 years;

(iii) for proposals for no new investment: the area would be reduced to just the residence and immediate surroundings, and a lease would be for a maximum of 30 years.

In

the case of urban land, the Minister said that town boundaries would be

rationalised to exclude large agricultural areas, and the remaining

urban land declared public land under the Land Reform Regulation. General management of town land would be under the responsibility of the Vila and Luganville Urban Land Corporations5.

Custom owners of urban lands would have representation on these

corporations, and would share in the revenues raised from them. Former

titleholders of developed urban land would be issued with leases

by the corporations, on terms and conditions which were still

being considered by the Government. The Minister concluded by advising

that he was working on the creation of a new system for

registering transactions in the former alienated lands, including

transfers, leases and mortgages.

Notable features of these early land policy statements and legislation are –

a) the Minister’s clear view that the "custom owners" of land in Vanuatu are

groups, not

individuals;

b) the clear intention that the general maximum for lease periods in rural areas would be 30 years, and would

only be for up to 75 years for

major development projects, and

only if the investor was prepared to enter into a

joint venture with the custom owners;

c)

it is also clear that the Minister’s power to enter into agreements on

behalf of custom owners under Sec. 8 of the Land Reform Regulation (now

Land Reform Act) was only intended to be exercised over alienated

land, not land which had never been alienated;

6d)

finally, it is clear that the Land Reform Regulation was only intended

to be an "interim" measure, until such time as the National Land Law

was prepared as required by Article 76 of the Constitution.

Reviewing

these land policies and legislation 27 years later, it is apparent that

many of these early principles have been seriously undermined. Findings

and conclusions will be drawn on the extent of departure from

these policies and legislative requirements in the next part of this

report.

3.2. Since independence

The

new land policies and legislation required identification of the custom

owners of alienated lands and the appropriate "alienator", and both of

these tasks inevitably led to difficulties. In the first case, the

fact that some plantation properties had been alienated for almost a

century made identification of the former custom owners problematic,

and local Land Committees were set up to try to resolve the

competing claims. In the case of identifying the "alienator" who was

entitled to negotiate with the custom owners, many former plantation

owners had been deported following independence because of their

political activities, and they were disqualified from being registered

as negotiators.

The Minister of Lands, Sethy Regenvanu, fought

hard for solutions which, while meeting the Vanua’aku Pati’s commitment

to the return of alienated lands, at the same time would

restore investor confidence, which he saw as necessary for future

agricultural development. In his autobiography in 2004, he wrote –

"I

had the dual task of trying to satisfy the expectations and wishes of

our people, while at the same time providing the existing and potential

foreign investors a degree of assurance that they could continue

to enjoy access to land, albeit under the new regime and different

laws."

7

3.2.1. Alienated land Act 1982

With a view to facilitating the process – and partly in response to the demand for alienated lands to be returned – the Alienated Land Act

was passed in 1982. It provided for the establishment of a

Register of Alienators (Sec. 2), in which any persons claiming to be

alienators had to apply to be registered (Sec. 3). Applicants had to

specify the option for which they wished to negotiate – basically,

a lease of all or part of the alienated land and/or payment for

improvements (Sec. 16(3)). Only if the custom owners were willing to

negotiate could the Minister issue a Certificate of Registered

Negotiator, under the Land Reform Act

(Sec. 16(2)). If the custom owners did not wish to negotiate a lease,

the value of improvements was assessed by a Lands Referee (Sec.

21), appointed under the Lands Referee Act.8 The land had to be vacated (Sec. 24), and the custom owners had up to 10 years to pay off any compensation (Sec. 17).

Persons

who failed to make an application to be registered as an alienator, and

deportees, were denied any rights as alienators, although the latter

could be entitled to compensation for improvements (Secs. 8, 9).

If the custom owners of alienated land could not be identified "within

a reasonable time", the Minister could appoint a person to act as

trustee on their behalf, and exercise their powers under the

Act (Sec. 25). In such cases, any moneys payable to custom owners

under a lease had to be paid into a special fund established by the

Treasury (Sec. 26).

While the above legislative arrangements

provided for the replacement of freeholds and other titles in alienated

land by leases, a major gap remained in the new land tenure system –

ie, provision for the registration of leasehold titles, and for

transfers of leases, mortgages, sub-leases and other interests in

registered titles. This gap was filled by the Land Leases Act

of 1983. The Act makes simple but comprehensive provision for all

the usual ingredients of a land registration law, the main distinctive

feature being that it is a law for the registration of leases and

dealings in leases, rather than for the registration of land ownership.

Apart from this fact, the Act is essentially a law which could have

been drafted for any country, and

it shows minimal evidence of having been tailored to

Vanuatu’s special circumstances. The term "lease", for example, is

defined to mean the grant "by the owner of land of the right to

the exclusive possession of his land", and the term "lessor" is defined as "the person who has granted a lease or his successors in title",9

neither definition giving any recognition to the fact that, in

Vanuatu, the land is either under custom ownership (if in a rural area)

or Government ownership (if in an urban area).

3.2.2. Land Leases Act

The Land Leases Act

contains Parts covering the usual subjects – the effect of

registration, dispositions, leases, mortgages, transfers,

transmissions, easements, subdivisions, etc. As with

any registration statute, the basic position is that leases and

other dealings in land only gain their legal effect after registration,

and upon registration the rights of the proprietor are "not liable

to be defeated" (ie, are indefeasible), and are held "free from all other interests and claims whatsoever" (Sec 15).10 Important qualifications on those rights, however, are contained in two provisions – those setting out implied agreements and those setting out overriding interests.

Notable among the implied agreements are –

- the

requirement that the lessee will not dispose of the leased land or any

interest in it "without the previous written consent of the lessor",

which consent shall not be unreasonably withheld (Sec. 40A);

- the

requirement not to use the land "for any purpose other than that for

which it was leased without the previous written consent of the

lessor", which consent shall not be unreasonably withheld (Sec. 41(i));

- the

requirement that, on determination of the lease, the lessee will

deliver up vacant possession of the leased land and any improvements

(Sec. 41(j)).

Notable among the overriding interests are –

- rights of way existing at the time of the lease’s registration (Sec. 17(a));

- rights of compulsory acquisition conferred by any law (Sec. 17(d));

- rights relating to roads conferred by any law (Sec. 17(h)).

Other notable aspects of the Land Leases Act are the following –

a)

lease terms shall not exceed 75 years, and if granted or extended for a

longer period shall be deemed to be for 75 years (Sec. 32);

b) every

lease must specify "the purpose and use for which the land is leased",

and "the development conditions, if any" (Sec. 38);

c) provision is made for regular rent reviews (Sec. 39);

d) the lessor has a right to forfeit the lease for a breach of its conditions, after serving a notice on the lessee (Sec. 46);

e)

a power in the Supreme Court to order "rectification" of a

registration, where it is satisfied that the registration was obtained

by fraud or mistake (Sec. 100).

It should also be noted

that some of the above protections for the lessors (ie, the custom

owners of the leased land) can be modified or removed, by the simple

device of expressly providing otherwise in the lease agreement.

However, the requirement for the lessor’s consent to any disposition of

the lease, or interest in it, cannot be modified or removed (Sec. 36).

The Land Leases Act finishes with a Schedule setting out registration fees. Subsidiary legislation introduced under the Act is the Land Lease General Rules and Land Leases Prescribed Forms. The latter consists of 21 forms, including for the following –

- an application for registration;

- a lease;

- a mortgage;

- a transfer of a lease;

- a caution.

However,

there is no requirement in the legislation that all their contents must

be included, and no changes be made to there most important contents.

A number of amendments were recently made to the Land Leases Act, with a view to improving the returns from leases for the lessors (custom owners) and the Government.11 Thus –

- the Land Leases (Amendment) Act of 2003

allowed the lease terms of public land to be extended to 75 years on

payment of a premium, and made provision for renewal of such leases

(Sec. 32B and C);

- the Land Leases (Amendment) Act of 2004 –

i.

introduced a different formula for calculation of the premium payable

for extension of the lease terms of public land (Sec. 32B(4));

ii.

prescribed a fee of 35% of the unimproved market value of the land at

the date of application, for an application for renewal of a 75-year

lease of public land (Sec. 32C(6));

iii. imposed the same fee of 35%

of the unimproved market value of the land for issue of a new lease of

public land which had either never before been leased, or was part of a

subdivision or strata title development (Sec. 32D);

iv. allowed a lessee to pay the first 5 years’ rent in advance, where the rent is fixed for a 5-year period (Sec. 39A);

v.

provided for payment by the lessee to the lessor (ie, custom owner) of

not less than 18% of the sale price upon transfer of a lease of rural

land, unless other arrangements have been made (Sec. 48A);

vi.

provided for a new "rural lease tax" of 1% of the unimproved market

value, payable annually by the lessee to the Government (Sec.50A);

vii.

increased the registration fees payable to the Government for the

creation or transfer of a lease from 2% to 6%, and for the creation or

transfer of a mortgage from 0.5% to 1.5%;

12 - the Land Leases (Amendment) Act of 2006, which reduced the fees for creation or transfer of a lease from 6% to 5%.13

While a number of these measures can be seen as trying to get a fairer

return for custom owners when the value of their land is increased (eg,

by a subdivision or strata title development), this is a difficult

matter for governments to manage.

Clearly, however, there is a need for all land revenues – rents, fees, premiums and taxes – to be rationalised.

The above three laws, the Land Reform Act, Alienated Land Act and Land Leases Act,

and the policies underlying them remain the basic land policy and

legislation in Vanuatu to this day. Over the next two decades there

were amendments made to those three laws, and four new laws were

introduced, but no new land policies were announced. The main changes

since 1983 are detailed below.

3.2.3. Land Acquisition Act 1992

Article 80 of the Constitution

enabled the Government to own land acquired by it "in the public

interest", and Art. 81 enabled the Government to buy land from custom

owners for the purpose of land redistribution. The Land Acquisition Act

set out the procedure for exercising the Government’s powers to acquire

land in the public interest. The first step was a decision by the

Minister that particular land was required for a "public

purpose", which the Act defined as "the utilisation of lands necessary

or expedient in the public interest and includes a purpose

which under any other written law is deemed to be a public

purpose". There then follows a sequence of steps, from initial

notification and investigation to notice of intended acquisition,

any appeals, an inquiry into compensation, any further appeals,

payment of compensation and taking of possession.

The procedure

under the Act has occasionally been invoked, to acquire both customary

land and on one occasion a lease, but agreement was reached on

compensation without the need to resort to compulsory acquisition.14

Governments in the Pacific Islands are extremely reluctant to acquire

customary land by compulsory acquisition, in part as a reflection of

the view that customary land is, essentially, unalienable. Nevertheless, the compulsory acquisition powers under the Act remain available, and the Act is not confined to customary land.

3.2.4. Land Reform (Amendment) Acts 1992 and 2000

These

amendments were an attempt to resolve the status of lands which, at

independence, had belonged to the British or French Governments, the

Condominium or a municipality. The Constitution

made no reference to such lands (which comprised the main urban areas

of Port Vila and Luganville), and it might therefore be thought that

they, too, reverted to custom ownership. But the Land Reform Regulation, in its original form, vested all such land (called "state land") in the Government as public land

(Sec. 9), and made provision for payment of compensation to the custom

owners "for the use of the land and the loss of any improvements

thereon", as well as other special benefits (Sec. 11).15

The implication was that the lands were only leased by the

Government from the custom owners, but by the 1992 amendment all the

provisions relating to the payment of compensation and other benefits

were repealed. The lands in question were simply vested in the

Government, without any qualification on their legal status or

provision for compensation. The implication now was that the lands were owned by the Government.

This

remained the situation until 2000, when another attempt was made to

deal with the outstanding issues affecting such lands. Without

referring to their legal status, the 2000 amendment introduced a

minimal provision for compensation – basically, allowing the Government

to determine the amount of compensation, taking account of "the market

value of the land and any other matters that it considers

relevant" (Sec. 9B). A right of appeal lay to the Supreme Court against

the amount of compensation determined by the Government. According to

recent newspaper reports, a total of VT 280 million was paid to

villages which claimed custom ownership of the Port Vila urban area,

but claims still surface.

3.2.5. Urban Lands Act 1993

The

decline of the strongly nationalist Vanua’aku Pati during the 1980s

allowed government to pass to its opponents, and this Act was

introduced by a coalition government led by the Union of Moderate

Parties (UMP). Its purpose was to allow the creation of urban zones in

addition to Port Vila and Luganville, with a view to encouraging

investment outside the two existing towns and promote

decentralisation.16 The Act has a

number of novel features, including provision for "Urban Communities"

and the compulsory registration of custom land in urban areas and

preparation of "development plans".

The Act was apparently

drafted outside the Attorney General’s Office, and moves were soon

under way for its amendment so as to clarify some aspects and bring it

into line with the Land Leases Act. In 2003, however, the Urban Land (Repeal) Act

was passed. At the time of writing, this repeal has still not been

brought into operation. The Act is, therefore, still in force,

but its future is doubtful.

3.2.6. Freehold Titles Act 1994

Similar

doubts surround the status of this Act, which was also introduced by

the UMP-lead government in a further move to free up urban land. It

allows indigenous citizens to acquire freehold titles over land in

urban areas, if they hold an "unconditional head-lease registered under

the Land Leases Act"

(Sec. 3). The legislation led to controversy, and doubts were raised

over its constitutionality although this was never challenged in

court.17 While it seems inconsistent with the Constitution’s emphasis on the customary underpinnings of land tenure, it is

certainly

arguable that the Act falls within the wording of Art. 75, allowing

indigenous citizens "who have acquired their land in accordance with a

recognised system of land tenure" to have perpetual ownership of

land. Once again, the uncertain status of "state land" in urban areas

presents a problem.

The main problem with the Freehold Titles Act,

however, is a practical one – the basic nature of the title depends on

the citizenship status of the title-holder. While the Act did try to

provide for the situation where an indigenous citizen holding a

freehold wanted to transfer the title to a non-indigenous citizen (by

reverting the title to a lease), this is obviously an unworkable

arrangement. Although the Act is still in force, it is understood

that no freehold titles have ever been issued.

3.2.7. Strata Titles Act 2000

Strata

titles legislation is designed to provide the benefits of registered

titles to units within different levels (or "strata") of a building. It

is usual, therefore, to make clear in the law that it only applies

to buildings. In the case of Vanuatu’s Strata Titles Act, the operative provision reads –

"Land

including the whole or a part of a building may be subdivided into lots

by registering a strata plan in the manner provided by or under this

Act." (Sec. 2(1))

While it would seem clear enough that

the land in question must include "the whole or a part of a building",

apparently this wording has been taken in Vanuatu to authorise the

approval of strata title developments over bare land. This is

using the strata title arrangements as a substitute for land subdivision, for which provision already exists in the Land Leases Act, Sec. 12(2).

Other provisions of the Strata Titles Act

make it clear that the normal requirements for subdivision do not apply

to strata titles (Sec. 3(1)), and that, upon registration of a strata

plan, separate certificates of title must be issued for each lot

in the plan (Sec. 2(2)). Notably, there is no requirement to seek the

approval of the custom owners of the land in question to the strata

title development. One major restriction, however, is that the

strata plan must be approved by a "consent authority" under the Act

(Sec. 4(3)), which means the relevant municipal council

or Provincial Government (Sec. 1). And the only person who can

apply for that consent is a lessee under an "approved lease" (Sec.

3(2)). An "approved lease" is defined to mean –

"a

lease registered or capable of registration in the Land Leases Register

for a term which, or which together with any option to extend the term

exercisable by either the lessor or the lessee, has an unexpired

period of at least 75 years [emphasis added] at the date the strata plan is to be registered over the land the subject of that lease." (Sec 1)

The

overall effect of these provisions seems to be that the only persons

who are capable of applying for a strata title development are those

who have converted their lease terms to renewable 75-year terms,

under the Land Leases (Amendment) Act 2003 (see above). Those long-term leases are only possible over public land – ie, generally, land in urban areas. By Sec. 32 of the Land Leases Act, lease terms over any other land cannot exceed 75 years, and if granted or extended for any longer period shall be deemed to be for 75 years18.

In 2003, the Strata Titles (Amendment) Act

was passed, making many technical amendments to the Act. Its main

purpose seems to have been to overcome any doubts that strata titling

could be applied to undeveloped land.

That completes this

account of the specific land policies and legislation introduced at

independence, and in the 27 years since. Many other laws have an effect

on land tenure and land use, and the main ones will be considered

below. They relate to surveys and valuation, land dispute settlement,

physical planning and foreshore development, and environment

protection. Before considering them, the specific land policies

and legislation will now be reviewed.

4. REVIEW OF THE LAND POLICY AND LEGISLATION

The

first point to note is that, after the early enunciation of land policy

at the time of independence, no further attempt was made to spell out

emerging policy. And once the basic land legislation was in place

by 1983, most reforms after that time were only adjustments to that

basic machinery. Such changes in policy which did take place were

mainly by a weakening of the principles laid down at independence,

and instead of policy development there was policy decline.

The 20 resolutions adopted by the National Land Summit in October 2006

reveal serious public concern over the increasing rate of land

alienation, ineffective regulation of land dealings and Government

failure to protect the public interest, unfair dealings, lack of public

awareness of property rights, and abuse of the laws.

The main

findings and conclusions about Vanuatu’s land policy and legislation,

as it has been applied over the last 27 years, are the following –

1. Interim arrangements.

What were originally intended as "interim" arrangements have remained

in place, without being improved or replaced. This applies particularly

to the arrangements for negotiation of leases, which were

originally designed for use only

with "alienators" – ie, those persons who were occupying lands

alienated during the colonial era, whose titles were abolished at

independence. Today, basically the same arrangements are being used exclusively for the negotiation of leases over customary land which has never been alienated before. The result is general dissatisfaction. According to a recent report –

- the

custom owners must put up with "lack of access to the leased land, the

extreme difficulties of regaining land once leased, multigenerational

leases with a 75 year term, and the ability of lessees to

subdivide leased land"; and

- private sector developers report that "100% of leased rural land has had problems associated with land ownership".19

The

legal requirements, forms and procedures need a major overhaul, to

adapt them to use for customary land which has never been alienated. A

model for how they might be adapted is provided by the Forestry Act

of 2001. In making provision for timber rights agreements (in Part 4

Division 2), the procedure for negotiation of leases was adopted, but

also modified to overcome its weaknesses.

2.

The Minister’s powers.

A particular example of the problem in paragraph 1 is the Minister’s

power to enter into leases on behalf of custom owners. This power was

clearly intended to be used

only in cases where there were unresolved disputes over

alienated land. Instead, the power has been used extensively by successive Ministers to

take the place of custom owners,

and enter into lease agreements into which the custom owners have

had no input. Research shows that 22% of the rural leases entered into

on Efate up to December 2001 were signed by the Minister (233 leases).

20

This is a recipe for disaster. Not only is it highly unsafe

to enter into a lease if the land ownership is disputed, the

custom owners are excluded from any involvement in the decision-making

over the lease, the rents and other benefits from it, and enforcement

of the lease conditions

21.

3.

Custom owners. The fundamental land tenure issues left unresolved by the

Constitution

in 1980 are still unresolved, 27 years later. In particular, the

uncertainty over the nature of custom ownership – is it by a

customary

group, or by

individuals

– remains to this day, and undermines all lease negotiations. On Efate,

the existence of land trusts and other bodies which are representative

of the custom owners has mitigated the problem,

22 but in all other cases there must be serious doubt over whether

all

the people with interests in the land being leased are being properly

informed and involved in the negotiations. All too often, it seems,

one or two senior males claim to be "the custom owners", and so

entitled to negotiate the leases and monopolise all the benefits

themselves.

4. Urban lands. The same uncertainties surround the status of public lands

in towns, and the entitlements of the former customary owners. While

the issues have remained dormant for some years, they may not remain so

permanently. Similarly, there is still doubt over whether indigenous

citizens can own freehold titles.

5. The Government’s role.

The balance between the freedom of custom owners to deal directly with

their land and the Government’s responsibility to protect them from

unfair dealings, as well as to protect the community’s and the

national interest, is not being managed satisfactorily. The nature of

the Government’s responsibility in land dealings, and how it is

exercised, needs to be spelt out in greater detail. Here again,

the inappropriateness of the Minister signing leases on the custom

owners behalf, while having statutory duties to protect their

interests, is demonstrated. There is an unavoidable conflict of

interest.

6. Enforcement of lease conditions.

A similar problem arises over the enforcement of lease conditions.

Whose responsibility is it? Who has the enforcement action? If the

custom owners lack this capacity, then the likelihood of non-compliance

is increased.

7. Terms and conditions of leases. There are many issues over the terms and conditions of leases. Thus –

a) Are appropriate land use and improvement conditions being imposed and enforced?

b)

The standard lease periods laid down in the Government land policy

statement (30 years for rural leases, 50 years for urban leases and 75

years for major investments and joint ventures) have been routinely

ignored. It now seems that the universal lease period – anywhere and

for whatever land use – is 75 years. Not only that but it seems that

some lessees have written in lease terms for longer than 75 years, by

providing for either a right of renewal or payment for

improvements. Neither of these is legally valid.

c) At the same

time, it is unsatisfactory for the position at the end of lease terms

to be left open. Clarification is needed on a lessee’s rights of

renewal, and what the options are in the final years of a lease term.

d)

Are the custom owners being approached for their consent when a lease

is transferred? If a lessee is a company, the lease can be

"transferred" by a simple transfer of shares, without the need to seek

the custom owners’ consent. This is an obvious avenue for abuse, which

should be closed.

e) While forms are prescribed for leases,

there is no statutory requirement that no changes can be made to their

most important contents. There is little point in setting out

requirements in forms, if one party to the document can simply

strike them out. All of the implied agreements on the part of a lessee can be struck out by the lessee.

f) No attempt seems to have been made to develop the joint venture concept. The political leadership put much emphasis on this device at independence.

8. Lease payments.

The position regarding payments by the lessees of land is

unsatisfactory. At present, it is partly left up to the parties to

negotiate, but it is mainly being determined by Government

legislative intervention. This is probably a response to the

perceived unfairness of arrangements which the lessees are negotiating

with the custom owners. There are a number of elements in the payments

lessees must make – rents and premiums payable to the custom

owners, and shares in a transfer price; fees for service (registration

fees); taxes (both national and municipal). These payments must be

reasonable and rational. At present, they are not.

9. Abuse of laws. The purpose of the Strata Titles Act

is clearly being abused at present, in its use for rural subdivisions

of undeveloped land. The genuine purpose of the Act, for issuing titles

to units in buildings, must be reinstated.

10. National Land Law. The Constitution in 1980 made provision for the National Land Law,

and the above review of the land policies and legislation shows the

pressing need to move forward with its introduction. Many of the

resolutions from the National Land Summit reinforce the problems

identified above, and the most appropriate way to deal with those

problems is in the National Land Law. Recommendations for how matters could be addressed there will be made below.

11. Strengthening rights in customary land.

A major gap in Vanuatu’s present land system is the absence of a law

for strengthening rights in customary land. Although the present system

provides for the registration of leasehold titles, there is no

provision for the custom ownership of any land to be registered. Not

only does this lead to doubts over whether the right custom owners have

entered into leases (a very common cause for dispute), but no

service is provided to custom owners who want to develop their own

land, and seek additional security of tenure. There is a range of

options available for strengthening rights in customary land, and

for entering into agreements (leases, mortgages, etc.) over those

rights. These are very sensitive matters, which require much

consultation and careful consideration. It would make sense for such

matters to be taken up, in the development of the National Land Law.

5. LAND-RELATED LEGISLATION

A number of Acts deal with the professional and technical land aspects of surveying and valuation.

5.1. Land Surveyors Act 1984 (as amended)

This

Act sets up a Land Surveyors Board and provides for the regulation of

surveyors and the conduct of surveys. Regulations passed under the Act

provide for survey marks and boundaries and other technical

survey matters, including the minimum areas, road frontages and

widths required for subdivisions.

5.2. Valuation of Land Act 2002

This

Act sets up the offices of Valuer-General and Principal Valuation

Officer, and provides for the valuation of land. The Principal

Valuation Officer has a duty to "ascertain the value of each parcel of

land in Vanuatu", and enter that value in the Valuation Roll (Sec.

7). Each taxing or rating authority receives a Valuation List relating

to land parcels within its area (Sec. 11), and the owners of the

parcels are notified of their right to object to a valuation (Sec. 19).

Objections are handled by the Valuer-General (Div. 5), from whose

determination an appeal lies to the Supreme Court, but only on a point

of law (Sec. 26). The Valuation Roll and Valuation Lists are public

documents (Sec. 33).

The Act also vests the Valuer-General with the functions previously performed by the Lands Referee under the Lands Referee Act

1983, which it repealed. They include the determination of rent payable

for a lease and any reassessment of rent, disputes over the value

of improvements, and "any matter … relating to the interpretation of a

provision in the lease" (Sec. 5).

5.3. Land Valuers Registration Act 2002

This

Act provides for the registration of land valuers and their

professional discipline. Valuing of land by non-registered persons is

prohibited (Sec. 13).

5.4. Land dispute settlement

Article 78(2) of the Constitution

provides that the Government "shall arrange for the appropriate

customary institutions or procedures to resolve disputes concerning the

ownership of custom land". Land disputes are a fact of life

everywhere, and this is particularly so in developing countries, where

traditional land tenure and land use systems are coming under many new

pressures (population increase, internal migration, monetisation of the

economy, etc.). The basic requirement is to have in place a land

dispute settlement system which allows disputes to be settled

efficiently, and with a degree of finality. Such a system must be

locally-based, participatory, simple to administer, affordable and

likely to receive the general support of the affected communities.

Among the main questions which need to be addressed in designing a suitable land dispute settlement system are –

- should the emphasis be on restoring the peace, rather than on determining land ownership?

- should responsibility be placed on the disputing parties to resolve their grievances, rather than on an outside body?

- should the dispute settlement forum be interested in the dispute, or neutral?

- should the emphasis be on mediation rather than adjudication?

- how binding should the decisions be, and on whom?

- how restrictive should the opportunity be for appeal?

- should lawyers be involved?

Both

Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands are reviewing their land dispute

settlement laws at present, and Vanuatu recently introduced a new

system.

5.4.1. Customary Land Tribunals Act 2001

In 2001, jurisdiction over customary land disputes was transferred from the Island Courts to Customary Land Tribunals, by the Customary Land Tribunal Act. These tribunals are constituted in different ways, depending on the location of the land in dispute. A single village land tribunal may only deal with land within the boundaries of that village, otherwise the dispute must be dealt with by a joint village land tribunal.

Appeals from the decision of either of these two bodies lie to a

hierarchy of land tribunals, depending on whether the land in dispute

lies entirely within a "custom sub-area", or extends over more than one

"custom sub-area", or "lies partly within one or more custom

sub-areas and partly within one or more custom areas that are not

divided into custom sub-areas".23 There is a final appeal from a custom area land tribunal to an island land tribunal.

The membership of the tribunals also varies, depending on the same criteria. In the case of a single village land tribunal,

it is made up of the "principal chief of that village" (as

chairperson), two other chiefs or elders, and a secretary

appointed by the principal chief (Sec. 8(2)). A joint village land tribunal

is made up of the "principal chief of each village", two other chiefs

or elders of each village, and a secretary appointed by the

two principal chiefs (Sec. 9(2)). A similar formula is applied to

the membership of the bodies handling appeals – the single custom subarea land tribunal, joint custom sub-area land tribunal, single custom area land tribunal or joint custom area land tribunal.

The membership of an island land tribunal

also depends on whether the disputed land lies within a single custom

area or more than one custom area. In the former case, there are six

members – the chairperson of the custom area council of chiefs, four

other chiefs or elders from the custom area, and a secretary appointed

by the island council of chiefs (Sec. 23(3)). In the latter case, there

are at least seven members – the chairpersons of each custom area

council of chiefs, four other chiefs or elders, and a secretary

appointed by the island council of chiefs (Sec., 23(5)).

The

Act includes provision for the determination of boundaries between

custom areas, and the approval of lists of chiefs and elders (Secs. 35,

36). A chief or elder is disqualified from being a member of a tribunal

in certain circumstances, including that he or she "has such business

or financial interests, or social, religious, political or other

beliefs or associations that will prevent him or her from applying

custom honestly and adjudicating impartially" (Sec. 37).24

Provision is also made for the procedure of land tribunals, how

decisions must be made and the orders a tribunal can make, and

allowances and costs for tribunal members (Part 6). The allowances are

set out in a schedule to the Act, and must be paid by the

disputing parties before the tribunal sits (Sec. 32(2)).

As for

the law which applies to land disputes, a land tribunal must determine

the rights of the parties "according to custom", but "the parties may

at any time try to reach an amicable settlement of the land dispute,

and the tribunal must encourage and facilitate any such attempts"

(Sec. 28). Although the object of the Act is to provide a system "based

on custom to resolve disputes about customary land’ (Sec. 1), a

possible limitation on the jurisdiction of the tribunals is the

wording of Sec. 7(1) providing for the giving of notices of a dispute.

It refers only to disputes "about the ownership or boundaries of

customary land". The power to handle disputes over interests less than ownership must be implied from the other provisions of the Act.

The Customary Land Tribunal Act

came into operation on 10 December 2001, and it was reviewed less than

three years later by a 5-person review team funded by NZAID.25 Among the team’s main findings were –

a)

the majority of landowners interviewed were supportive of the tribunal

system, but still "lacked confidence and knowledge" in its

implementation;

b) a minority of chiefs, however, saw it as "undermining their authority and the customary procedures";

c)

a number of village and area councils were having difficulty in using

the system "because of disputes regarding the rightful chief"; the work

done by the Malvatumauri to identify rightful chiefs "appears to have

exacerbated the problem";

d) problems over land leases were a

major cause of land disputes; private sector developers "reported that

100% of leased rural land has had problems associated with land

ownership".

The review team made eight major recommendations, including –

- that the Customary Land Tribunal Act

be retained, but strengthened in its provision for applying customary

procedures "as the preferred option for resolving customary land

disputes" (Rec. 5);

- that the Government continue to

work with the Malvatumauri on processes to facilitate "the

identification of rightful chiefs so that kastom can be applied to customary land disputes"; as a first step, the Malvatumauri could assist with the recording of kastom related to land ownership (Rec. 6);

- that

the Island Courts be available when neither the customary processes nor

the land tribunals are able to resolve disputes, but not as the preferred option (Rec. 7);

- that a National Policy on Land be adopted (Rec. 3).

By

early 2007, further progress has been made in implementing the Act,

although tribunals had still not been introduced in much of the country

(including around half of Efate). A detailed "Administrative Procedure

Guidelines" sets out the administrative steps involved in implementing

the Act, which is the responsibility of the Customary Lands Office in

the Department of Lands. A further NZAID-funded review was being

planned, to identify the support required to fully implement the Act.

Some of the main issues which still need to be addressed are –

- Problems in identifying chiefs, and clarifying their authority in the modern context.

In Vanuatu, chiefs are officially recognised as having authority in a

hierarchy – from village to area, island, provincial and national

levels.26 There are area councils of

chiefs, as well as island, provincial and national councils of chiefs,

the latter also known as the Malvatumauri. Chapter 5 of the Constitution

provided for the National Council of Chiefs, with a "general

competence to discuss all matters relating to custom and tradition"

(Art. 30 (1)). Article 31 required Parliament to enact a law to provide